On the night of Palm Sunday we Maronites celebrate a rite which we can call “Arriving (or Arrival) at the Port,” or “Reaching the Harbour,” or some combination of these. The first thing to note is that in liturgical time, the night of any Sunday is going to be Monday: from sunset on Sunday is liturgically Monday according to the Semitic way of reckoning days. So Arriving at Port is therefore the very first rite of the Week of Sufferings, also called “Passion Week” or “Holy Week.”

Then, let us look at the rite itself, which at first unfolds like the divine office. At the outset, I there are some major differences between the Arabic and the English in the text which I have. For example, in the mazmooro, there is practically no point of contact between the translations. As but one example, the second Arabic stanza refers to the presence of the Archangels Gabriel and Michael. They are not to be found in the English. I do not know which text is original or what was to be found in the Syriac, but the English seems to me to be inferior.

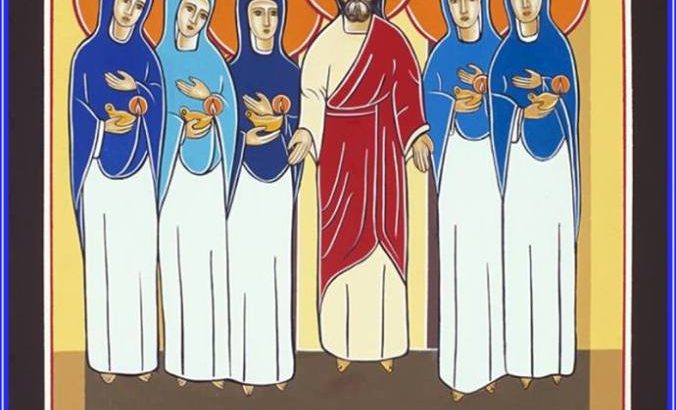

With that qualification, the rite begins with the celebrant and the people outside the church doors, which are closed. They have lights, e.g. candles and lamps. The first prayer likens us to the virgins of the parable in Matthew 25, with a prayer that we may be like the wise virgins who vigilantly await Christ the Bridegroom with their lamps lit, and ready with their flasks of oil (faith, hope, and love).

The next prayer likens Christ to the harbour of salvation and safety. It refers to the world as a tumultuous or stormy sea, but says that Christ Himself has drawn us to Him, bringing us over the waters, and beseeching Him to enlighten us with the Beatific Vision in heaven. We then chant the “Hymn of Light” attributed to St Ephrem. The prayer which follows this returns to the image of the virgins’ lamps, that our lights may never lack the oil of divine love. The next hymn is to “Jesus Christ, Source of Light,” a hymn which is also found in the Book of Offering for use before the Divine Sacrifice.

From this point, the rite follows the ramsho prayer service (vespers), e.g. one of the responsorial psalms of evening light and sacrifice: “Your word is a lamp to my feet and a light to my path” (Psalm 119:105), and a hymn before the Hoosoye or incense prayer. This picks up the themes of the Harbour of Safety, Christ the Good Physician God the Eternal Light, the loss of light with the Fall, and the recovery of the light and the image of God by taking off the old man and assuming the new; a freely rendered allusion to the Wandering in Sinai motif of following the cloud by day and the pillar of fire by night; and once more, the parable of the virgins with their lamps and flasks. A hymn refers to “the Ark of Lent,” and to meeting Christ in suffering. The Etro prayer returns to the concept of the Harbour of Salvation, and the mazmooro before the scripture readings portrays the Church as a ship sailing to the experiences of good and evil, in the English version, whereas in the Arabic, the emphasis is on meeting the saints in heaven and enjoying the Beatific Vision.

The Epistle is Hebrews 6:13-20, chosen possibly because it refers in v.19 to hope as the anchor of the soul. The Gospel is that of the parable of the Wedding Feast and the waiting virgins. You will recall that at the end of that parable the door to the banquet is closed, and the foolish virgins knock for admittance, but in vain.

After this, the celebrant approaches the church doors with the Cross in his hand, and knocks three times, and the deacon chants: “O Christ our bridegroom, we have come out to meet You. Lord, Lord, open for us!” The response is “Fill our hearts, Lord, with the light of Your Kingdom.” It also refers to the Good Shepherd who opens the gate, and to reaching the Harbour of Salvation. The then enter the church, with the final hymn and prayers, with the Our Father, and a reference to the Harbour of the Holy Church.

No one knows how the rite originated, but it was common through the Syriac world. It seems to me that the main theme, or rather, the only unifying theme, is that of hope. Most particularly, the anchor of hope in Hebrews 6:19 calls for the idea of a journey at sea, beset by storms, but safely achieved through the faith. The parable of the Wedding Feast and the concept of safely arriving at port have much in common: the sailors must be diligent and wakeful, like the virgins: the port is a destination, as is the wedding banquet; and light is needed for both – one can hardly reach a destination one never sees, and the sea-side temples in ancient Phoenicia doubled as lighthouses: they lit bonfires on the rooftop.

My own conjecture, for what it is worth, is that the rite draws on the Phoenician history of Lebanon. The Phoenician is the only relevant religion of the area I know of which had rituals where the sailors would sing hymns and offer thanksgiving for their safe return. There is in fact an entire book on the Phoenician religion of seafarers, “Each Man Cried Out to His God”: The Specialized Religion of Canaanite and Phoenician Seafarers, by Aaron J. Brody (1998). I am fortified in this conjecture by the recent publication of Robert D. Miller’s The Dragon, the Mountain, and the Nations, which shows how knowledge of the ancient Canaanite myths were incorporated into the Old and New Testaments. In other words, ancient Near Eastern material, from the Phoenician world, had been used in scripture: it is therefore possible that other Phoenician material was used later on.

In summary, the liturgy for Reaching the Harbour includes several themes: from the natural world it takes the motif of safely surviving a dangerous sea voyage and the joy of reaching a peaceful port. From the New Testament it borrows the parable of the Virgins, and from the faith it takes the virtue of hope to hold it all together.

But what does it all mean? Arriving at the harbour does not mean the end of all striving: we are yet to experience Passion Week. What it means is that we have come through Lent not to escape suffering but rather to be entitled to share in the sufferings of the Lord. This is, I think, why it does not come on the night of Easter Saturday. The Resurrection is the revelation of the glory of God. Before we come to that point, we must be worthy to share in it. When the sailor reaches the port his work is not yet done. He must dock the ship, he must see the goods safely off the ship and sent to their destinations, and help the crew come safely home. Rather than meaning the end of his work, reaching the harbour concentrates the labour, simplifies and clarifies the job to be done. But he takes hope: he is on dry land, and the end of his task is at hand if he keeps his calm.

Interesting perspective linking it with Phoenician practices. I was always curious around the naming and timing of this rite. I wonder what else we have incorporated from the mountains of Lebanon.