Parts one, two and three of this series appear at http://www.fryuhanna.com/2022/01/28/ad-orientem-liturgies-part-i/

http://www.fryuhanna.com/2022/02/04/ad-orientem-liturgies-part-ii/

http://www.fryuhanna.com/2022/02/24/ad-orientem-liturgies-part-iii/

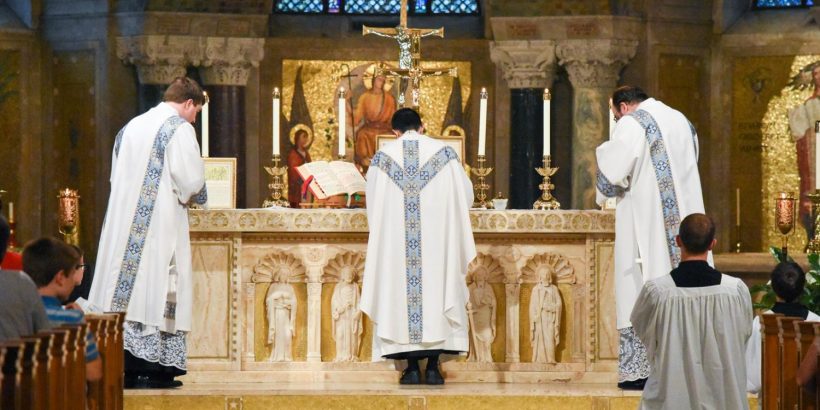

The Maronite and traditional Latin liturgies will have to be taken separately, and then compared. Once the Anaphora commences, the Maronite liturgy is conducted with the priest standing either behind the altar, or else before it, i.e. ad orientem. In the vast majority of cases today, the priest stands behind the altar. In fact, unless the altar is a “high altar”, i.e. affixed to a wall so that the priest cannot get behind it, then the liturgy is invariably conducted from behind the altar. It does not have to be like that. The priest can celebrate the liturgy ad orientem at a free-standing altar. I have seen the Maronite Patriarch do so. But it is rare.

I have to briefly describe the Maronite liturgy because without having this clearly in mind it will not be easy to grasp the point: the Maronite altar is ornamented by a series of decorous and simple movements and gestures, and the object of celebrating the Eucharist from behind the altar is not to highlight the priest but to allow the richness of the liturgical actions to be seen. For this, it helps to have the altar more visible. The centre of attention is not the priest, but the altar and the actions upon it.

These movements and actions include numerous blessings of the congregation (usually with the Sign of the Cross, holding a Hand Cross), the extension of hands, the signs made at the peace (hands upon the altar, and offerings, exchange of peace with hands joined – not shaking hands), lifting the hands and looking upwards, joining hands at the breast and bowing, the reverent management and elevations of the oblations at the Institution Narrative, and the two portions which most move me: the actions of the epiclesis and the Fraction, Signing, Sprinkling, Mingling, and Elevation.

The epiclesis features the prayer mo d.Hee.loy šo3.to Ha.bee.bay (How awesome is this moment, my beloved), and the kneeling behind the altar with the invocation 3a.neen mor.yo, 3a.neen mor.yo 3a.neen mor.yo (Hear us, O Lord), the kissing of the altar before the priest redresses himself, and the signing of the Cross over the oblations. This is a distinctive feature of the liturgy of some of the Eastern Catholic Churches: they ask God to send to Holy Spirit to hover over the offerings and to change them. It is an explicit evocation of divine action. The prayers are not addressed to the Holy Spirit directly, but to the Father to send Him (that it is the Father rather than the Son would follow from the prayers of the kneeling being based on the Old Testament pleas of Elijah.)

The Fraction and so on will not be apparent in their detail, but the basic trajectory of the action is: that the host and the contents of the chalice are mingled, and then the offerings are elevated and the broken host and the Precious Blood are offered for the adoration of the congregation. The oblations are elevated a third time at the “Holy gifts for the holy,” and then the communion follows. The actions are not just extremely important, they are absolutely critical. Whereas the faithful could almost never understand the Syriac of the liturgy, they could understand and follow the actions, hence the Maronite Eucharistic liturgy was basically a sort of demonstration of the truth of the mysteries, that the oblations were offered to the Father, and transformed by the divine action of the Holy Spirit, then the Body and Blood of the Son are worshipped, and the liturgy reaches its climax when these are distributed to the people.

Of course, just before the communion, there is another series of penitential prayers in which the people bow their heads before the altar. The priest stands with his arms outstretched, and the people lower their necks. It can be done ad orientem, but the liturgical action makes more sense if the priest is behind the altar.

Now, if I am correct that what happens in the Maronite liturgy is that the priest stands behind the altar to accentuate that this is an altar upon which the divine sacrifice takes place, then for him to stand before the altar would detract from the altar and the action upon the corporal and the management of the sacred vessels and the oblations. So, although many see the priest facing the people as imposing his personality upon the congregation, this is, I suggest, an acceptable price to pay or hazard to run for the immeasurably greater good of highlighting the divine action upon and over the altar. This also has the corollary that the front of the altar should not be dressed up too much: that too, distracts from the Eucharistic miracle and the stages through which it passes.

When we come to Latin liturgy we find something similar in essence but quite other in detail: the reality of the divine sacrifice is shown there by the contrast between the hiding of the action and the revelation of the host at the “Ecce Agnus Dei …” behold the lamb of God.

The Mass of the Catechumens being complete, the traditional Latin Mass comes to the Mass of the Faithful. The priest kisses the altar, turns to the congregation with a “Dominus vobiscum,” says “Oremus” (Let us pray), then returns to the Gospel side to read the Offertory verse. That is, true to the spirit of that liturgy, he turns to the people to invite them to pray, and then reads the Offertory in the loud tone. He then unveils the oblations and prepares the corporal and vessels for the following action.

Certain things are seen by the people, and others are not. For example, when the pall, in the colours of the day’s liturgy is placed against the altar card, the people see this. But when he makes the Sign of the Cross over the corporal, and the positioning of the host upon the corporal, the people see only his reverent bowing and perhaps the movement of his elbows. I repeat, this is right and entirely within the spirit of this liturgy in which the interplay between the secret and the revealed is paramount.

At this point, the congregation see the servers bring up the wine and water, and the priest pouring from the cruets into the chalice, and blessing the water. This is not seen in the Maronite liturgy, because it is performed in the sacristy. But note that the people can see the priest, who is side-on, thus showing once more that it is a gross over-simplification to say that the traditional Latin Mass is all celebrated by the priest with his back to the people. Those who say this are either ignorant, or else have not pondered the reality.

Abouna,

If anything is evident from your articles on this topic, it’s that there are a number of subtleties and angles to consider in this whole ad orientem question.

But, in any case, would you agree with the assessment that there seems to be precedent evidenced by traditional Maronite architecturefor the priest facing the congregation? (Which would, I suspect, have a quite different liturgical and theological rationale than the changes which have transpired in this regard in the Western–Roman Church since 1970.)

In conversation with a Maronite priest / Canon lawyer I know, the suggestion was raised that if this be the case it may owe to the Maronites’ monastic origins (e.g. in Chapter the community would stand “around” the altar). Elsewhere, I’ve seen there may be some precedent in traditional Maronite architecture, wherein the altar (representing Christ) stands in the midst of of an apse (representing the Father), with the priest taking his place “in Heaven”, as it were, between apse and altar, facing the congregation.

Appreciate your thoughts,

j.t.b.

Well, I cannot add much more at this stage. You write that this person told you that in chapter the community would stand around the altar. But is that correct? How do we know this? Yes, I do refer to that symbolism in some of my posts – that seems to be a constant in the East. It seems to me that the most important natural symbol of all is the morning sun breaking through the windows above the altar. That is simply sublime.

I meant to say above, “precedent evidenced by traditional Maronite architecture”