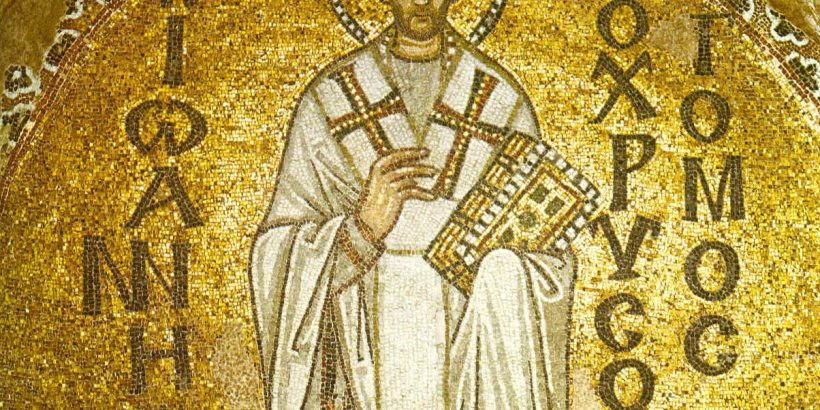

St John Chrysostom, Feast 13 November

St John Chrysostom is one of the most important of all the many famous bishops from Antioch. He is celebrated in the Maronite Liturgy which has an Anaphora in his name. Yet, although he was the pride of Antioch, he was never bishop of Antioch. He was a priest there, and a very important one. But he was called by the Emperor to be Patriarch of Constantinople. When he was deposed, he was sent into exile on the Black Sea, and never returned. In the Orthodox Church, he is considered one of the three universal teachers, together with Ss Basil the Great (c.329-379) and Gregory Nazianzus (the Theologian, c.329-390).

St John was probably born in 349 in Antioch, and died on 14 September 407. The name “Chrysostom” or “Gold Mouth” was given to him because of his eloquence. His father died young, but his family was considered important and wealthy. John was given an excellent Greek-language education, and was probably a pupil of Libanius, a famous orator who was hostile to Christianity. He finished studying with Libanius in 367, at the age of only eighteen.

Although his mother and may be his father, too, was Christian, John was not baptised until 368, when he was baptised by Bishop Meletius, who had been exiled. John had probably been prepared for a career in the civil service, like his father, but gave that up to work as the bishop’s aide. During this period, John was living at home with his widowed mother, but studying scripture with Diodore (who died about 390). Diodore taught not in an ordinary school, but what was called an asketerion. It was not a monastery, but the young men who studied there regarded one another as ‘brothers.’ They are thought to be related to the Syriac phenomena of the “sons of the covenant” and the “daughters of the covenant” (benai/benat qyama). They were celibate, abstained from wine and meat, wore special clothes, and devoted themselves all day to religious duties, as they were not allowed secular employment.

Meletius appointed John a “reader” in 371, so that he could proclaim the Old Testament and the Epistles during the liturgy. His next promotion six years later, was to the rank of deacon. The next year, 372, he moved to some mountains near Antioch where an elderly Syrian monk directed him in the ascetical life for four years. He then withdrew to a cave where he lived as a hermit for two years, and learnt the scriptures by heart. This move from the city may have been prompted by the fear of being forced to be ordained a priest.

This six years of great privations ended in 378, when Meletius returned from his third exile, and John from his hermitage to Antioch. He had fasted so long and so hard that his health was damaged, his stomach and kidneys never to fully recover. However, he never lost his love of the solitary life. He later wrote: “Monks contribute to the salvation of their fellow men, helping by their penances and their prayers those who are in charge of the church.” This seems to me to mean that the monks help the church indirectly; they pray to God and mortify themselves, and he honours and rewards their labours by helping His Church.

These men, Chrysostom among them, lived in a group of small huts and cells which were close together, so that each person had their own accommodation, but could be said to be “next door” to each other. They remained in their lodgings for all night and much of the day. They were woken at cock crow, and prayed assembling four times a day to glorify God. They also studied scripture, and did various jobs (e.g. agriculture and book copying). The money they made from these was donated to the care of the poor. The food was very simple: basically bread and salt, with perhaps oil, vegetables and lentils. They wore goat and camel skins and slept on straw, and often under the sky.

For about four years, Chrysostom lived this “semi-communal monasticism”, then pushed himself to retire to a cave in the mountains for two years, learning the scriptures by heart, but apparently never lying down during that period, and trying to avoid sleep. But he ruined his kidneys, stomach, sleep, and it would appear, his circulation, for from then on he was very sensitive to cold. It is known that alcoves were built to help a person to stand but never lie down. This could not go on without premature death, and he returned to Antioch, probably at the end of the year 378. Resuming his office of reader, Chrysostom became a deacon in 380/1, serving until 386 when Bishop Flavian, Meletius’ successor, ordained him a priest in early 386 when he was probably 36 years of age. He served as a priest in Antioch, and became famous as a preacher. It is thought that in this twelve year period he wrote the approximately 900 sermons that have survived, although, so far as I can see, the evidence is not clear.

It is known that the twenty-two sermons preached up to Easter in the year 387 came from Antioch. Some statues in that city had been taken down, which caused fear in the city, as the Emperor Theodosius was expected to take revenge. And he did, executing even children and leading figures. Many Antiochians of all classes and ages fled. Except for the churches, which were filled, the city seemed to be desolate. He preached frequently, during the week as well on Saturdays and Sundays.

To his surprise, in 398 he was made Bishop of Constantinople. I doubt that this unexpected elevation, engineered by the imperial eunuch Eutropius, has ever been well explained. John was effectively kidnapped from Antioch, apparently because the people would have been expected to complain at his removal. A lot of his care in Constantinople was apparently how to counter the Arians, who conducted night processions and sang hymns. He spent so much time travelling, attending to various matters in the Eastern section of the Empire, that he had to appoint his archdeacon as administrator and the Syrian bishop Severian as preacher. immediately established himself as a reformer.

As bishop, John was unusual: he did not take part in the social life of the city, but rather studied scripture and devoted himself to charitable works (caring for widows, virgins, deaconesses and the poor and establishing hospitals and hostels for travellers). He tried to reform the lives of both clergy and laity, exhorting the laity not to store up excessive wealth. He also cared for the liturgy, and established night liturgies and processions, even taking care that the Gothic (barbarian) population of Constantinople had liturgies. Against his will, he had to become involved in political affairs, in so far as political and religious affairs could be separated then in Constantinople. He made enemies by his asceticism and exhortations to morality and modesty – a matter which the Empress Eudoxia especially resented.

It was such matters that had John Chrysostom exiled. The history of his exile is rather convoluted. The bottom line is that after much trouble, he was put on trial at the Synod of the Oak in 403.Although the Synod went against him, he still served as bishop, and was not banished until 404, first to Cappadocia and eventually to the Eastern shore of the Black Sea, dying on route, in 407, at about the age of 58. At the insistence of Pope Innocent I (402-417), his memory was rehabilitated and his bones taken first to Constantinople, and finally to Rome.