I thought it might be worthwhile taking a few more words for research today.

Aback, must mean something to do with the back. But exactly what? Already by 1944, the third edition of the Shorter Oxford Dictionary said that it was chiefly used as a nautical phrase, and meant “backwards.” On the sea, a ship taken aback was caught by a head wind, and its sails were pressed back against the mast. Today, the phrase “taken aback” means “disconcerted, surprised.” The 7th edition of the Macquarie adds that in Australian usage it means “suddenly taken by surprise.” This fits in with the poetic description on the Shorter O.D., “to be caught in front suddenly through a shift of wind, and driven astern; figuratively, to be disconcerted by a sudden check.” That is, there seem to be three concepts together here, (1) suddenly (2) placed at a disadvantage, and (3) being in fact checked.

Chambers Dictionary of Etymology, edited by the learned but not always reliable Robert K. Barnhart, says “the figurative sense caught suddenly by surprise appeared in 1840 in Hood’s Up the Rhine. This is a reference to Thomas Hood (1799-1845), the English humorist. He was a popular author, but still one can only wonder as to how a phrase introduced in one not terribly important book has entered the language. I think it must have something to do with the value of the phrase. Almost no one who uses it would realise that it had any reference at all to ships, masts, sails, and winds, but the sound of it, short and decisive with the cutting “ck” at the end, makes it fitting for its purpose.

One last point: Chambers says that its use developed from the Old English phrase on baec, meaning “at or toward the back.” However, it does not mean that today, in the sense that it is not simply a substitute for the phrase “towards the back.” If someone told us to go “aback the bus,” we would understand what they meant, but it would be a very odd way of speaking. Today, we only say “go to the back of the bus.” But more than that, our wise and beloved friend the Anglican priest Walter William Skeat, former Elrington and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon in the University of Cambridge, says that the prefix was “a-” in its second sense, that while one manuscript of the old usage has on bakke, others have abak. The prefix a- had at least 13 values, and the second of these was on; for which Skeat cites afoot, meaning on foot. When one turns to his entry for on, he demonstrates that is is cognate with the Greek preposition ana, so that the two English prefixes a- (in its second sense), and on- may not be so dissimilar as they seem. Robertson’s NT Grammar also relates the Greek ana to the English on. He says: “The fundamental idea seems to be “on,” “upon,” “along,” … and this grows easily to “up.”

This is quite fascinating. Only two days I posted a piece on the importance of associations for us, and here is a concrete example of how associations enter into everyday use of the language and allow one word to be used for something it had not originally meant. The history of this word also illustrates the role of one writer, here Thomas Hood, in causing change in the language.

Heist comes from the word “hoist.” Before we come to its meaning, its history is this: in British usage, to “hoist” could refer to housebreaking, because it often happened that one burglar (“the hoister”) would let another one climb onto his back, so that standing on the hoister’s back, the second burglar could get into a high window. Then, the word “heister,” which may only have reflected a dialectal variation in pronunciation, came to mean a “shoplifter,” and by 1927, “heist” was being used as a verb to mean “rob, steal.”

Now, the Macquarie gives the meaning of “heist,” as “rob, steal.” As we can see, that is not wrong. But I think the word has rather a more glamorous nuance than just robbing and stealing. The example of usage which the Macquarie offers refers to the “great heist from the National Gallery …” I think that is significant, as is the same dictionary’s noting of three phrases: “heist book,” “heist movie,” and “heist novel.” I would say that to use the word “heist” when speaking of robbery and stealing is to imply something more than mediocre about it: perhaps it was larger, more complex, called for more ingenuity, or was audacious.

It is an interesting example of how a dialectic difference can make a significant difference in the meaning of a word, and enrich the language. “Heist,” after all, is far more colourful than “hoist.”

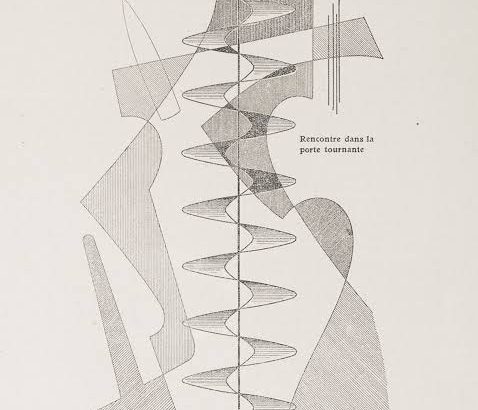

Helicopter is a literary innovation. It comes from two Greek words, helix, helikos meaning “spiral,” and pterōn meaning “wing,” so “spiral wing.” It was coined in 1861, and was employed by Jules Verne in his 1886 novel, Robur the Conqueror. I think it rather a beautiful word, even if the reality is less so. Properly speaking, a helix is any spiral or coiled form (e.g. the curved fold of the rim of the outer ear), or any “spiral advancing around an axis,” Shorter OED. But is the sound of this word which renders it sublime. The illustration with this page is attributed to Man Ray.

Joseph Azize, 1 February 2020